Continuing from my previous blog, looking at ways in which an historical novelist can try and achieve authenticity in their writing, today I am looking at portraying the social context of the time, and describing physical details, such as clothes and food.

Social context

What was it like to live in the fourteenth century? The popular modern view might well be “nasty, brutish and short”, which, while bearing some measure of truth, suggests an unrelenting grimness that I feel unreasonably excludes everyday humanity and emotion.

It is true that life expectancy at birth was short, children being in constant peril from accidents, untreatable illnesses, the effects of poverty, and natural disasters. But if an individual survived childhood and reached the age of around twenty or so, he or she might then hope to live until at least middle, if not old, age.

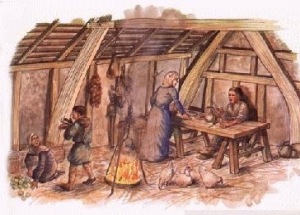

Perhaps most people did live in environments that, to us, would seem horribly dirty, foul-smelling and dark – the image of a gloomy, dank and stinking hovel comes to mind. Sometimes historical novels or films are criticised for presenting too clean a picture, and it is also true that, in my novels, I don’t dwell at length on the nastiness of people’s living conditions, but I also don’t shy away from it when appropriate. It is undoubtedly correct that peasant houses were generally dark from a lack of windows, and smoky from the central hearth, and even great houses would be cold and draughty, but there seems to be no reason to imagine that people of every station in life did not make every effort to ensure their homes were as comfortable as possible.

In my descriptions of peasants’ homes, I think I show clearly enough that they are cramped, d ark and smoky, and, in bad weather, cold and damp. But my readers might think I have some sort of obsession with the problems of “laundry”… For, aware that peasants would be unlikely to have more than a couple of sets of clothes, and imagining what it must have been like to be outside in the rain and then coming home all wet, with just a small fire in the hearth (no radiators or tumble dryer…), I concluded that drying clothes must have been a nightmare! No history book I have read so far has told me how they handled it, so I deduced that they would have made some attempt at drying their clothes around the fire, on some sort of rack, perhaps, and that they possibly slept in their clothes, sometimes at least, to help them dry out a bit. It seems a pretty ghastly prospect! Yet what else might they have done? (If anyone does have some information, I would love to read it.)

ark and smoky, and, in bad weather, cold and damp. But my readers might think I have some sort of obsession with the problems of “laundry”… For, aware that peasants would be unlikely to have more than a couple of sets of clothes, and imagining what it must have been like to be outside in the rain and then coming home all wet, with just a small fire in the hearth (no radiators or tumble dryer…), I concluded that drying clothes must have been a nightmare! No history book I have read so far has told me how they handled it, so I deduced that they would have made some attempt at drying their clothes around the fire, on some sort of rack, perhaps, and that they possibly slept in their clothes, sometimes at least, to help them dry out a bit. It seems a pretty ghastly prospect! Yet what else might they have done? (If anyone does have some information, I would love to read it.)

If we time-travelled into a mediaeval town or village, we would undoubtedly find the whole environment pretty unpleasant. However, in my novels, the narrative is seen through the eyes of the characters, so, even if their homes and general environment were smelly and uncomfortable by our standards, they surely would not recognise it as worthy of remark, unless it was in some way unusual. So, any lack of reference to unpleasant environments is deliberate, as we are looking at life through the characters’ eyes – eyes that surely would not notice what was commonplace.

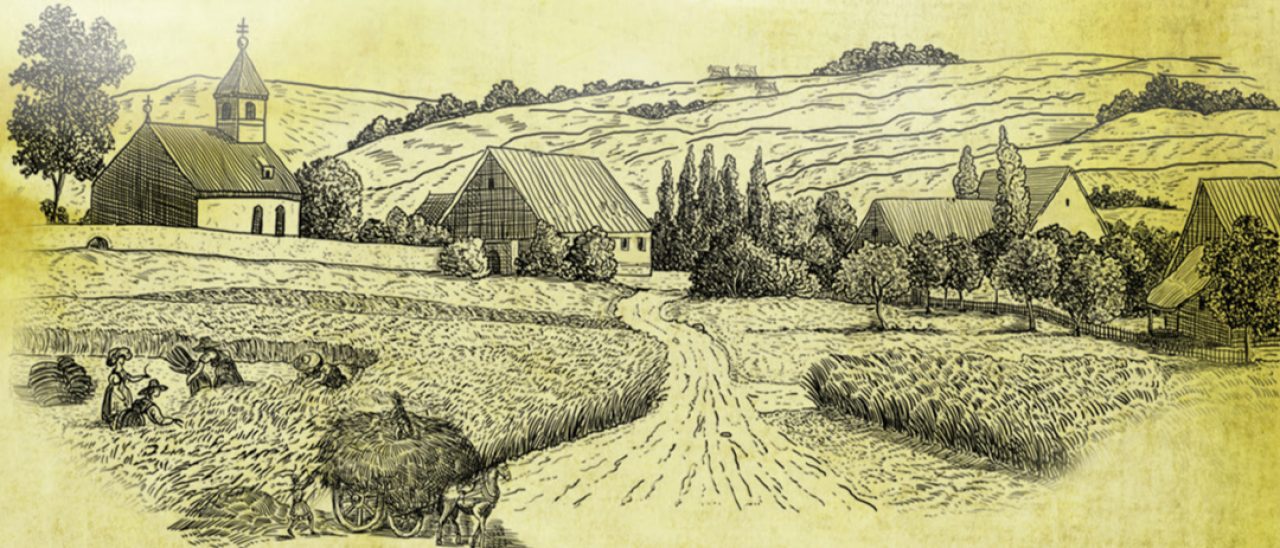

Many of my characters in all my novels do refer to the commonplace difficulty of walking out of doors, because of course medieval roads were generally not well-maintained, particularly in rural areas, and one can only begin to imagine the devastation to roads and pathways wrought by winter weather and constant rain.

It might be summer, and dry today, but it had been raining on and off for weeks and the gulleys at the sides of the road still ran fast with rainwater. The road itself was muddy and tricky to negotiate, and she picked her way carefully to avoid slipping into the deep ditches. It was not far, but by the time she reached the manor gate, Alice’s boots were soaked through to the inside.

Fortune’s Wheel p.37

It was not, presumably, always quite so bad, although it must be true that, without paved roads, travel in the Middle Ages, especially in wet weather, would often be an arduous, uncomfortable affair, and I have always borne this in mind.

Indeed, weather plays a strong role throughout my novels, for it must have affected the daily lives of medieval people far more than it does us (here in England, at any rate). In some cases, especially in parts of my as yet unpublished novel The Nature of Things, it is fundamental to events. A very useful book for understanding historical weather is John Kington’s Climate and Weather, which contains detailed descriptions of weather from the first century BC to 2000 AD, and has a summary for each year of the fourteenth century.1 It is perhaps unlikely that many readers would know what the weather was like in, say, 1305, but being able to draw on a “factual” description of it does, I feel, bring a sense of authenticity.

The warm, dry summers of recent years continued the run of good harvests. But, this year, the sun’s heat is not warm but oppressive, the hay crop has failed and beasts are dying in the fields from a lack of fodder. Tempers are fraying and, despite my efforts with the village youths, the very heat seems to spur them on to even more ill-tempered brawling.

The Nature of Things p.48

Trying to imagine myself into my characters’ shoes, into the minutiae of the context of their daily lives, is part of what I find so fascinating about writing about the past, and is what I hope brings a sense of authenticity to the story.

Physical details

Describing accurately what we know or can deduce about how people lived, their homes, clothes, food, tools, working practices, is perhaps not too hard to achieve. If writers read enough history, visit museums and, where appropriate, study contemporary documents, they stand a fair chance of getting the physical picture of a period right, although even the most careful researcher might slip up, or choose one version of the “historical truth” over another, which some readers might question. That is true of any fiction, of any period.

So what happens if a writer gets a detail wrong?

Noticeable anachronisms – events not yet happened, artefacts not yet invented, ideas not likely to have entered anybody’s mind – must be avoided. However, I would guess that many readers do not always recognise anachronisms. Some evidence for this can be found in book reviews, where 5* reviewers may say nothing negative about a book, while 1* critics of the same book appear to exult in pointing out every historical failing. The fact is that, for readers who do notice problems, the writer’s credibility as a portrayer of authenticity may be immediately compromised.

As an example, I was surprised to find mention of potatoes in Julia Blackburn’s The Leper’s Companions, a novel (shortlisted for the Orange Prize) set in England in the year 1410. This may seem cavilling, but potatoes did not arrive in Europe until the mid-sixteenth century. Blackburn also refers to a ‘shift…with the lace around the sleeves and neck’, apparently belonging to a peasant woman, which seems unlikely for the time. Yet, it seems, if a reader likes a story enough, these details may not matter, even if they are recognised. On the back cover of The Leper’s Companions, an anonymous critic described it as ‘profoundly researched as all [her] work’; and an Amazon reviewer said ‘It is exquisitely written in lean & learned detail…’2 Indeed I found myself happy enough to overlook apparent glitches in research because of the other qualities of Blackburn’s book. It is an intriguing story, and the strangeness of the world she created is fascinating, if not very naturalistic, thus showing that the balance of acceptability is different for different readers.

However, my novels are intended to be naturalistic, and I wanted to show the physical details of “everyday life”, with food and clothing just two aspects of the physical that can help lend an air of naturalism and authenticity.

For example, here, the narrator describes a meagre meal taken during the privations of the famine.

Ma ladles pottage into a large serving bowl, and puts it down in front of him. ‘There’s a scrap of that good bacon in there,’ she says, ‘so eat up, husband.’

He turns to look at her and smiles. ‘A little,’ he says, picking up his spoon. He dips it into the pottage and, filling it with the gravy, raises it slowly to his mouth and tips it in. ‘It’s good,’ he says and smiles again.

‘But you took none of the bacon,’ says Ma, standing over him like she used to when we were children. ‘Nor any of the turnip.’

‘Let the children have some first,’ says Pa, signalling to us to dip our spoons and take our share. […]

When the bowl is almost empty, Ma fetches a small hunk of the coarse bread she’s made from barley mixed with ground up peas and beans, and cuts it into five pieces, three larger and two smaller, and, handing one to each of us, bids us wipe the big bowl clean.

The Nature of Things pp.85-86

There are many references throughout my novels to clothing: kirtles, cloaks and headdresses, cotehardies and surcoats, boots and wooden pattens, fleece hoods and workmen’s coifs. Most items of clothing are mentioned more or less in passing, but one or two are described in a little more detail.

For example, when I discovered a suggestion that peasants might have used hoods made of fleece to keep off the rain, I realised it might not be “true”, but it seemed likely enough and had an authentic ring.

For example, when I discovered a suggestion that peasants might have used hoods made of fleece to keep off the rain, I realised it might not be “true”, but it seemed likely enough and had an authentic ring.

Then I pull on one of the sheepskin hoods Ma’s laboured to make us all. It made her fingers bleed stitching through the skins, and Pa complained at the waste of fleeces. […]

It’s true the fleece hood keeps my head dry, though I hate the sheepy smell and scratchy itch of the unwashed, oily wool so near my face.

The Nature of Things p.75

However, although physical details are hugely important, it is not usually factual (in)authenticity that is the main concern of historical fiction’s detractors. As I will show in my next blog, it is the depiction of historical thought-worlds that can be trickier to write.

(Note: I have discussed this and other aspects of writing historical fiction in my PhD thesis, Authenticity and alterity: Evoking the fourteenth century in fiction, University of Southampton, Faculty of Humanities, 2015 <http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/383484/>)

References

1 John Kington, Climate and Weather (London: Harper Collins, 2010), pp.221-232.

2 Reviewer “A Customer” (2002), Amazon Customer Reviews, The Leper’s Companions <http://www.amazon.co.uk/product-reviews/022405127X/> [accessed 25th June 2014].

An interesting post. I agree that we must try and get into the mindset of our characters, who will take the day-to-day details of their lives for granted. My childhood home was heated by open fires only, so no radiators. If it was a really wet day, you didn’t do any laundry, but sometimes the rain was unexpected. If this happened, or someone was caught in the rain, a big wooden clothes-horse was opened out in the kitchen and the wet clothes put to dry on it. Your peasants might also have put up clothes lines either in the cottage itself or in an empty out-building,

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your comment, Catherine. Yes, I too remember the clothes-horse around the coal fire – many decades ago! Perhaps that was the image that was in my mind when I described the drying of clothes in my novel? I love trying to imagine these details of their daily lives, when there is no specific evidence of what they actually did. It’s certainly part of what makes writing historical fiction such fun!

LikeLike

Pingback: Authenticity in historical fiction (V) – Carolyn Hughes Author