It’s been a while since my blog was actually about writing, and I thought it was time to put that right. As it happens, this week, when I am coming to the end of the writing and editing process of the second of my “Meonbridge Chronicles”, seems a suitable moment for me to tell you a little about this new book, and to attempt to justify, or at least comment on, why it is taking me so long to get it to publication!

The current title of book 2 of “The Meonbridge Chronicles” is A Woman’s Lot. That title might change, but I’m pretty happy with it, because the story is indeed about the diverse fates – happy or otherwise – of women. It is set two years after the end of Fortune’s Wheel, picking up the lives of four Meonbridge women, all of whom – if you have read it – you will have met before in Fortune’s Wheel.

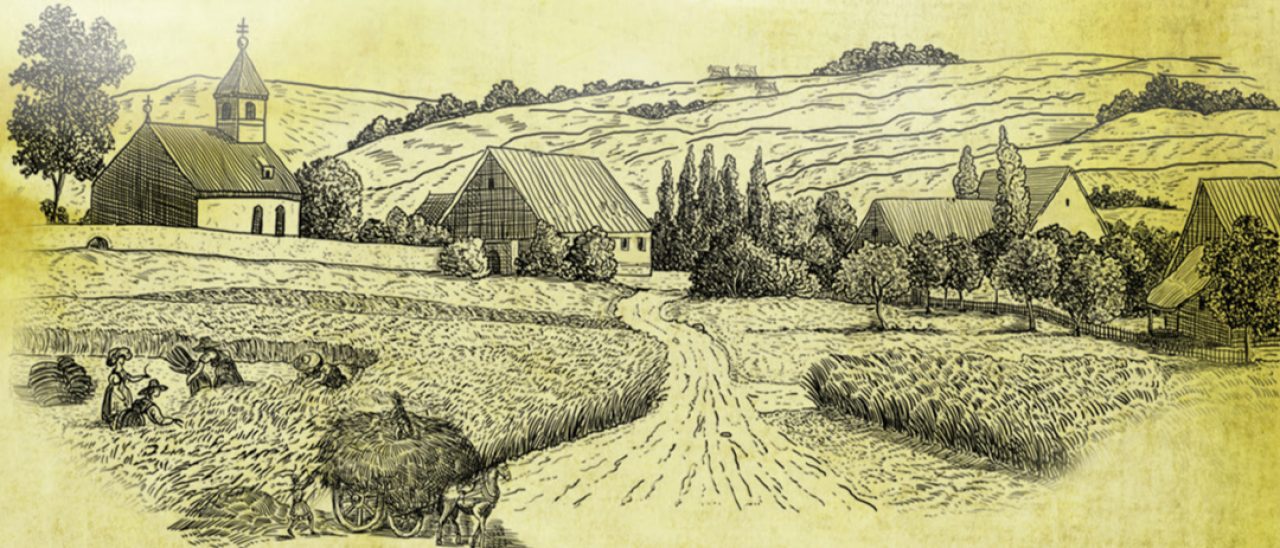

I showed in Fortune’s Wheel, and have discussed in one or two of my blogs that, after what we call the Black Death, the huge loss of population countrywide meant greater opportunities for those who had survived, for them to earn more money, take on land they couldn’t have had before, enter new occupations. The rigid feudal structure of society was already breaking down and the devastation caused by the plague accelerated it. Working people were no longer willing to accept the constraints imposed by their feudal lords, of giving unpaid service, having no control on wages and not being permitted to leave their manor.

All this did change. People began to move about in a way they’d not really done before, seeking higher pay, better work, greater opportunities. And this applied to women too.

But I mustn’t overstate the case. Some historians have said that the later fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were some sort of “golden age” for women, in terms of their opportunities, although others dispute this. Perhaps the opportunities for women were greater in the towns, and especially in London. Maybe, if there was a golden age, it did apply mostly to those living in the city. In the countryside, change probably took longer, and, anyway, opportunities for women to become, say, artisans or businesswomen would not have been so commonplace in rural communities.

But I mustn’t overstate the case. Some historians have said that the later fourteenth and fifteenth centuries were some sort of “golden age” for women, in terms of their opportunities, although others dispute this. Perhaps the opportunities for women were greater in the towns, and especially in London. Maybe, if there was a golden age, it did apply mostly to those living in the city. In the countryside, change probably took longer, and, anyway, opportunities for women to become, say, artisans or businesswomen would not have been so commonplace in rural communities.

However, I have combined what I have read about the lives of medieval working women, with what I imagine might have been their situation. With half the population dead from the plague, it seems almost inevitable that everyone – men and women alike – would, initially at any rate, have had to step into the “manpower breach” and work at whatever was needed to return the life of the community to some sort of normality. Which is why, in my novels, and particularly in A Woman’s Lot, I have women trying to – or at least wanting to – contribute in ways in which they might not have done before.

However, once the immediate crisis was over, even if the feudal system had fallen away, society was still society, and that meant men in charge, men with all the rights and privileges, and women still essentially subject to their rule, and to the rule of their husbands. And that too is reflected in A Woman’s Lot.

But this is a novel and not social history, so my female characters do of course struggle with themselves and with the constraints that others – men! – impose upon them. They remain – I hope – essentially mediaeval women in the reality of the lives I give them, but I see no reason why they should not also have desires and ambitions, which may or may not be fulfilled. It is the lot of all fictional protagonists, to want something and to struggle to achieve it. Whether or not they do so is what gives a story its tension and motivation…

I won’t say any more, but I do hope that sounds potentially intriguing. And makes you eager to know when you will be able to get your hands on it…

But I’m sorry to have to say ‘not yet’.

I had hoped to be publishing it this summer – round about now, I suppose. And when those lovely readers of Fortune’s Wheel told me how much they were looking forward to my next book, I probably said, ‘Oh, definitely, 2017!’

But in fact I’m not sure now that it will be available even this side of Christmas. The editing phase is by no means finished. I’m close to the end of my own editing, but I’m then sending it out to a couple of beta readers and a critique partner for what I hope will be some critical feedback (in the sense, I hope, of “involving or requiring skilful judgement as to truth, merit, etc.”, rather than “inclined to find fault or judge severely”), and my editing process will then continue. After that, it will go to a professional editor, followed of course by yet more editing…

Then, because I’m not directly self-publishing but will, as with Fortune’s Wheel, use a professional publisher to produce my book, the publication process will take another three months or so. So you can see that time will pass, and it may well be 2018 before I hold my new book in my hands…

Which is disappointing, of course, but – as other writers tell me endlessly – it cannot, must not, be rushed. I have to ensure that the book is as good as I can make it.

But why does it take so long?

Some writers, after all, put out two or three books a year of similar length to mine. So am I just a slow writer? Yet some others take much longer. Famously, Donna Tartt has published just three novels in twenty years: The Secret History in 1992, The Little Friend in 2002, and The Goldfinch in 2013. She certainly didn’t rush! Not that I am comparing myself with Donna Tartt. But I suppose a novel simply takes as long as it needs to take…

Having said that, I am pretty keen to get this one out, and then the next one. So what is holding me back? A few thoughts…

A particular writer I know writes very fast. She is currently writing books in series, which of course I’m doing too. She has also many published books – she’s a very experienced writer.

An advantage of writing a series is one’s growing familiarity with the world in which the novels are set and at least some of the characters, so you do not have to create those aspects of the novel from scratch each time. Although there are still likely to be some aspects that are new – in my own case, for example, for A Woman’s Lot, I had to learn about coroners and courts, and the work of carpenters.

An advantage of writing a series is one’s growing familiarity with the world in which the novels are set and at least some of the characters, so you do not have to create those aspects of the novel from scratch each time. Although there are still likely to be some aspects that are new – in my own case, for example, for A Woman’s Lot, I had to learn about coroners and courts, and the work of carpenters.

An advantage of being an experienced writer is that the techniques of writing – while never, ever, easy – undoubtedly do become a little easier. If you’ve successfully published a dozen books, then you probably have a fair idea of how to structure a book, how to plan and pace, how to write coherent, flowing sentences and choose the “right” words, how to make your characters come alive on the page. As with any skill, the more you practise writing, the more proficient you become. Whereas, with just one published novel (although I have completed, or half written, four others) I am simply much less practised at my craft. But I am learning, and hopefully improving all the time, so the “nuts and bolts” of writing will eventually become almost second nature.

So, that is one reason for me taking so long to write my novel. I am still practising my craft and it simply does take time.

But it is not the only reason. For I am also quite pernickety.

I read a fair number of books, many of which I enjoy simply because of their wonderful story. Sometimes the writing itself is wonderful too, and I notice how very good it is. But more often, and I think this is important, the writing is so good – well-structured, well-paced, good characterisation, proficient grammar, mellifluous, or at least coherent, easily-read sentences, good word choice – that the reading experience is such an easy pleasure that I can simply let myself be drawn into the story. And I think that this is what you want and expect from a good novel, whether it’s historical fiction, a romance, a thriller or whatever: to get entirely lost in the world that the author has created.

Conversely, what you don’t want as a reader is to be constantly thrown out of the illusion of the story, to have your pleasure interrupted, by being pulled up short by, for example, hard-to-fathom sentences, poor or plain wrong choice of words, what Jane Austen called “infelicities and repetitions”, sloppy grammar or punctuation, or frequent typos. Yet this pulling up short happens to me really quite often and, I have to say with much regret, more so with self-published novels than with those traditionally published. The latter are not immune from errors, but they do seem much less frequent.

I find this very disappointing. Yet, sometimes, if I go to Amazon to see if other readers have had the same unhappy experience of a particular book, I find that the answer quite often is, they haven’t! Or, if they have, they haven’t mentioned it in their review. So did they not notice? Or didn’t they care? How I would love to know the answer…

We new indie writers are urged often to ensure our work is properly edited – professionally edited, if possible. But surely those books with so many “infelicities” cannot have been? Yet, if the readers of those books don’t seem to mind, the obvious question is, how much does it really matter?

Well, I think it matters to agents and publishers. They definitely notice. It matters also to professional, if non-traditional, publishers like SilverWood, who won’t take on a book that has clearly not been very carefully edited.

Well, I think it matters to agents and publishers. They definitely notice. It matters also to professional, if non-traditional, publishers like SilverWood, who won’t take on a book that has clearly not been very carefully edited.

And, anyway, it matters to me! Partly, perhaps, because I spent more than thirty years in a career – technical writing – where good, clear, grammatical, well-spelled writing was expected, both of me and by me. After all, good writing aids reading and understanding and, in the context of a novel in particular, enjoyment. Bad writing can make a book difficult to read, possibly confusing, and may result in it being thrown across the room!

I don’t think it’s necessary to get too heavy about all this. I’d be mortified if anyone thought I was setting myself up as the “grammar police”. This is not about being critical of others for the sake of it, it’s about writers producing the very best books for their readers to enjoy.

So, I am – yes – quite pernickety. That is not to claim that I achieve perfection – but I do aim for it. What I do is read and reread my work, many times, stripping out or rewriting “infelicities” of every kind. As part of my editing process, I work my way through one or more of the writing advice guides that I have. Two, very different, but useful, books spring to mind. First is Self-editing for Fiction Writers by Renni Browne and Dave King. The chapters include basic advice on show and tell, dialogue, interior monologue, point of view, each with a checklist to help you in your editing. The Word-Loss Diet, by Rayne Hall, is quite a small book and formulaic in style, but its simple premise is to help you cut unnecessary words from your draft and, my goodness, it works. Even if you think your book is well-written, you may still find that it’s full of words you really can do without. The result of the ”diet” is simply a more tightly-written book. That’s all it does. But I do recommend it.

All this reading and rereading does of course take time. A lot of it. But, for me, it’s most definitely worth it. It has always been important to me that, when I publish, my books would be the best that I could make them. That’s all.

So I’ll keep at it and hope that A Woman’s Lot will be up on Amazon’s virtual shelves before too long.

Being one of your readers who loved book one and is waiting for book two, I think you do a very fine job. But I see your point. Although I write my books quickly (sometimes) I am also still learning about the processes of editing and so on. I do find it a disadvantage sometimes that I have not had the learning that you and other authors have had, therefore, sometimes I can make a mistake and never see it. When another author read one of my books and then refused to leave a review, even though she told me privately she liked the story, because of all the ‘repeats’ in it which drove her mad, I was gutted. However, as a result of that, I now have a proof-reader who is excellent (not the aforementioned author) and I have leaned much through her proof readings. I still have corrections to make in some older books but at least now I can have the confidence that when I put a new book out, it is in good shape. Writing quickly is all very well but the editing and proofing stages are more important, in a way, and it’s right that they take more time. I’m grateful to that author and others who have guided me in the art of finishing a book properly – and I don’t mean how to end a story!

LikeLike

Thank you so much for your thoughts, Jeanette. It’s a learning process for us all, I think, and I’m sure that the more we do (write), the better we get at it, as with any skill. But I suppose we do need to recognise where any problems might lie, which is why I make use of those books I mentioned – and others – to help me check off some of the things I don’t get quite right the first time around. I guess all of us benefit from help of some sort, whether it’s from books, or what I might call “expert readers” of various sorts. Writing is a lonely job and I do think it’s important to get others involved in the process. This will be the first time I’ve used “beta readers” and a critique partner, though it’s clear that many other writers always use them. It’ll be nerve-wracking, of course, wondering what they’ll say, but worth it, too, if it gives me some guidance about where my novel is and isn’t working!

LikeLike

Pingback: Motorways or country lanes? – Carolyn Hughes Author